Dance

Maha Ashtami is the traditional Sandhya Aarti and Dhunuchi Naach. Sandhya Puja is one of the most important aspects of Durga Puja. Multiple priests perform the ritual. Dhunuchi Naach which involves dancing with a Dhunuchi along with Sandhya Puja is a tradition that no one wants to miss. As the sound of Dhaak fill the air, the celebrations of this special day reaches its peak, reminding us that this is after all the most awaited day of Durga Pujo.

Sindoor Khela : The married women engage in Sindoor Khela which involves smearing Sindoor on the foreheads of each other, feeding each other with sweets and hugging each other as an indication of a blissful and happy married life. The loha, shakha and pola worn by married women is also touched with the sindoor

The accessibility to dance itself can never be restricted and dance as it is cannot be copyrighted.

With today’s dancers creating their own classical items as well as thematic productions, things have changed. The terms choreography and choreographer are used even in the Indian dance scene, often very randomly. When does a Jathiswaram, Varnam or Tillana become the intellectual property of the person creating a new version of it? And if it does, because some country’s regulation, not understanding the history behind it, allows it, can these names, which describe particular items of the classical Bharatanatyam repertoire be patented? Whose composition rights should be considered for music? And if a particular musician has composed the music and has the right to claim copyright for it, should not someone make sure that the name of the raga itself cannot be patented? The same applies to themes, which are nothing new, but are being revived or reinterpreted. And if the question of copyright should come up in such cases, it should be closely scrutinised as to what is being copyrighted and under what name. That part, which an individual can claim as innovative creation belonging to or becoming his / her intellectual property, cannot be more than a tiny bit, because classical items are set choreographic patterns set by masters, mostly generations ago and called accordingly, but allowing renewal of both musical and thematic content.

Comparison to examples of copyright issues as known in the West can therefore only be applicable to the modern concept of choreography / choreographer, where a completely new movement repertoire/style or format of presentation is created today. But even where contemporary choreographers are concerned, is there one who has not tapped from the movement repertoire that has existed in some discipline somewhere in the world? The idea/notion of using it in a specific fashion is perhaps new and individual. Thus, the dance form in itself cannot be copyrighted by the derivative of new creations can be.

When I choreograph a stage production for an official theatre, since these copyright rules exist in the West, I have to sign agreements. Do I keep or forego my ‘intellectual protection rights’ should I leave the production, especially after it is premiered? My source for inspiration and new ideas is dance in its most basic form as known in India and elsewhere and life itself. Due to these reasons if I opt to forego these, someone coming in later could claim these were his/hers. Pragmatically thinking, yes we do live in such a world. Therefore it would be worthwhile to consider signing the agreement under the condition that anyone else staging it with a similar movement repertoire later cannot claim these rights either, thus making sure that Indian dance is protected from restriction alien to it. But ‘copying’ for the sake of it is an age-old phenomena, isn’t it? If someone claims a copy as hers/his, he/she will find ways and means to do it, immaterial of copyrights already existing, because one can always claim that there is a subtle change. Similarly anyone can claim that a particular idea was originally hers/his and therefore cannot be used by others. Even here someone taking over the ideas can argue that there are subtle changes. Therefore neither claimer can really win if they are wanting to patent something as universal as dance itself. Any intellectual property right can apply only to a very particular aspect, really very difficult to define.

SO SIGN AN AGREEMENT WHEREBY THOSE WHO RECORD IT CANNOT MONITISE ON IT.

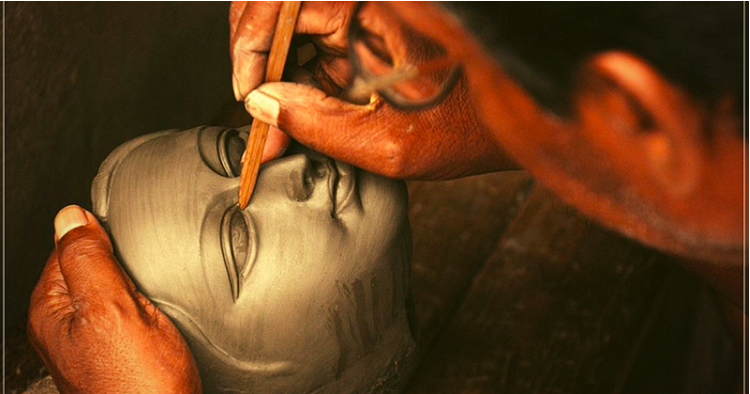

Dhunuchi Naach or Dhunuchi dance is performed to thank the Goddess.

Many Durga Puja organisers hold Dhunuchi Naach competitions for participants, and visitors too, at the pandals, which see enthusiastic participations and prove to be big draw every year.

Dhuno is considered a purifier, a reason it’s offered to gods. However, it had a traditional use in daily life too. Dhuno purifies the air and hence was used as a traditional mosquito repellent. Many households still use this. All you need is this earthen pot, some dried coconut husk and dhuno,

Documenting dance has not been a diligent practice the world over although the West perhaps has fared much better in that department with a wealth of librettos, rehearsal notes, programme notes, newspaper reviews and illustrations of ballets dating back to the 19th century that give us a peek into the dance world of the time.

In 1928, Rudolf Laban from Germany came up with a notation system that described and analysed movement and helped document dances. Subsequently, the Dance Notation Bureau was born in 1940 that used the Laban notation to preserve choreographic works including those of George Balanchine, Jose Limon, Bill T Jones, etc.

The tradition of the arts in India, on the contrary, is founded upon the idea of manodharma (loosely translated as self-improvisation), which pushes the boundary for individual expression. Even if a dancer performs the choreography of a celebrated master or guru, she may add to it her own interpretations or little embellishments. It’s not surprising then that there wasn’t felt ever a compelling need to preserve a piece of choreography as is. However, one must give the devil its due. Government supported Doordarshan Archives and IGNCA (Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts) are perhaps the only resource centres that house recorded performances of the biggest stars from the constellation of Indian classical dancers since the 1980s. All this is to say that unless a thing of beauty and transience such as dance is not made tangible then, claims of ownership and authenticity become difficult.

When we speak of a dance, it is not just the actual physical act of movement in whatever form or style, but the entire package that includes the intellectual and aesthetic framework of the piece, ideas expressed, costuming, set design, music and then of course, the actual sum and substance of dancing. Unabashed stealing of intellectual property is a problem as old as the ages and also one that cannot be proven easily with incontrovertible proof. “I am copied every season. The colour of my costumes, the props I use, it goes on but I do very bold work with feminist tones and most dancers don’t venture in that area. I don’t really worry all that much anymore,” says Anita Ratnam, “Often, a ‘mudra here or a group pattern’ maybe tweaked a little bit thus making it very challenging to prove plagiarism,” she adds.

According to Dr. Jayaprada Ramamurthy, senior flautist from Hyderabad who studied copyright law in India with respect to music and dance for a research fellowship, unlike music, which has an established system of notation for a composition making it possible for a musician to lay uncontested claim to an original piece of work, no such system exists for Indian dance. She suggests that senior dancers from various forms got together and created a unique system of notation for each style much like Laban that would then make it easier for choreographies to be preserved as it were and prevent intellectual shoplifting.

The other trouble is, how would one even know if one’s work has been lifted? For Keersmaeker, Beyonce is a well-known entertainer and her brazen use of the former’s work came to light in no time. In obscure cases, one would definitely not know and in such cases, ignorance perhaps is bliss.

The Supreme Court in Academy of General Education, Manipal and Anr V. Malini Mallya (2009) has clarified that a ballet dance forms part of dramatic work as defined in section 2(h) of the Indian Copyright Act of 1957. The act also provides protection to a dancer if recordings of her performance are reproduced without her consent. However, copyright law of choreographic work is still in a fledgeling state. There are choreographers, who are copyrighting their works by applying to the Copyright Office, which falls under the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion. Copyright of original dance choreography lasts for 60 years, counted from the year following the death of the author. The copyright owner’s remedy lies before the civil court in the event of a copyright infringement. Infringement is a cognizable and a non-bailable offence, which carries a penalty of up to three years imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 2 lakhs

a selection, coordination, or arrangement of functional physical movements such as sports movements, exercises, and other ordinary motor activities” did not represent the type of authorship intended to be protected as choreographic works under the US Copyright Act. However, a “composition and arrangement of a related series of dance movements and patterns organized into an integrated, coherent, and expressive whole” could rise to the level of original choreographic authorship. (WIPO – Stating Ruling for DANCE/ YOGA)

Even if simple yoga or exercise routines are unlikely to meet the minimum threshold of originality in most jurisdictions, a film or description of such a routine may qualify for copyright protection, as may a compilation of photographs of the routine’s individual movements. Additionally, exercise brands can leverage the value of their trademarks and make a profit from teaching their routines to others (through “train the trainer” programs) or from licensing their brand to fitness centers so that people familiar with a particular program know what to expect from the centers’ workout sessions.

The brand released a digital video showcasing how the community comes together for the devotional ‘Dhunuchi naach’, which is integral to Durga Puja celebrations. The video opens with visuals of a majestic view of Durga Maa in focus. With a sound of the ‘Dhunuchi dhak’ in the background, the camera brings the viewers’ attention to the smoke coming from Dhunuchi or the earthen pot, representing the beginning of the Puja. The next frame shows enthusiastic Kolkatans performing the traditional Dhunuchi dance to the tune of the dhak by holding the Dhunuchi pots that billows the fragrant smoke.

The video closes with visuals from the on-ground event that captures the success of the record-setting dance relay marathon performed by the ‘ChotPote’ (energetic and active) people of Kolkata.

Sindur Khela

The women are usually dressed in white saris with red borders and adorn traditional jewelries.[6] Each of the women perform arati and smear the goddess’ forehead and feet with sindur. They also offer her sweets and betel leaves.[3] Following that the women smear each other’s foreheads with sindur.[7] Then they put sindur on each other’s shankha,[7] pala[7] and noa,[8] the conch shell, coral and iron bangles respectively, which are worn by the married Bengali Hindu women. Then they smear each other’s faces with sindur. Finally they offer sweets to each other as prasad.[7] According to commonly held belief, if a woman plays Sindur Khela by following the proper custom, she will never be widowed.[9] Sindur Khela symbolizes the power of womanhood in protecting her husband and children from all evil. Through the ritual of Sindur Khela, the Bengali Hindu women pray for long and happy married lives of each other.[1][6] Family tiffs and petty quarrels between neighbours are settled through this ritual.[2] Unmarried women and widows are barred from participating in the ritual, but a recent campaign by the Calcutta Times has revived the practice of just women – be it married, widowed, transgender individuals or women of the red-light area, to play with Sindoor to show that this is a universal bonding for all women, all sisters and not restricted only to married women.[10] In some parts of West Bengal, Sindur Khela is celebrated before Vijayadashami. In Dubrajpur, the Sindur Khela is celebrated on Mahasaptami itself. After bathing the nabapatrika and the following ritual worship, sindur is applied on the forehead of the goddess. After that the married women engaged in Sindur Khela.[11] In the village of Bijra near Memari in Purba Bardhaman district, the family pujas of Ghosh and Bose family celebrate Sindur Khela on Mahastami. The tradition is almost 500 years old. After the ritual worship on Mahastami, the entire married womenfolk of the village celebrate Sindur Khela. Many people from adjoining areas came to Bijra to see this ritual dhunuchi nritya, or a frenzied dance with the censer, to the accompaniment of feverish dhak rolls. Many puja traditions also organize contests for the best dance, where some performers may go with as many as three dhunuchis – the third one held between the teeth. Dhunachi arati also known as “dhoop arati”.

Clothing

- Ladies choose the typical red bordered white sarees, gold ornaments and a red Bindi, Sindoor and Alta being a must for the married. Men prefer white or golden kurta-pajama in cotton or Tussar material paired with a stole, wearing Dhoti is a must for most.

- Loha, shanka and Pola

Textiles

Muslin production in Bengal dates back to the 4th century BCE. The region exported the fabric to Ancient Greece and Rome. Bengali silk was known as Ganges Silk in the 13th century Republic of Venice.[6] Mughal Bengal was a major silk exporter. The Bengali silk industry declined after the growth of Japanese silk production. Rajshahi silk continues to be produced in northern Bangladesh. Murshidabad and Malda are the centers of the silk industry in West Bengal.

After the reopening of European trade with medieval India, Mughal Bengal became the world’s foremost muslin exporter in the 17th century. Mughal-era Dhaka was a center of the worldwide muslin trade. The weaving of Jamdani muslin saris in Bangladesh are classified by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage.

Modern Bangladesh is one of the world’s largest textile producers, with a large cotton based ready made garments industry.

Laal Par Shada Shadi

The saree is white on the body and has red borders (paars). Bengali ladies in the city as well as around the world are experts in styling themselves in the traditional drape of “Aat Poure” style and complete along with gold jewellery, red bindis and aalta on the hands and feet.

If you’ve spotted multiple women wearing laal paar shada sharee (white sari with a red border), you’re probably standing in the middle of a Durga Puja pandal. The lal paar shada saree, easily associated with Bengali women, are made in the state’s Murshidabad district and worn by married Bengali Hindu women across the length and breadth of India during auspicious occasions.

But this seemingly benign traditional wear is not without some problematic riders. The most obvious one being that the laal paad sharee, traditionally, is meant for the ‘shodhoba’ or women whose husbands are still alive. The colours were forbidden for widows, who were rarely made part of the Durga puja celebrations, and spinsters.

“Red would be the marker of married women, coupled with the “pola” which was derived from the red gala used to seal letters. If one were to go back to a time when Bengal was far less affluent, this would be the most economical way of doing so. Clothes were a marker of social position. In the context of Durga Puja, this gets highlighted further as Durga is supposed to be the daughter coming home to parents. And, this marker, would move across classes. A poor person would wear a cotton laal paad sharee, a rich person would wear a silk or gorod variation of it,” Abeer Gupta of School of Design, Ambedkar University, the red and white combination is a story of dyes told The Indian Express.

Renowned textile historian Jasleen Dhamija explains how the combination of colours is connected to the goddess Durga. “The red and white combination saree is supposed to signify the mother goddess. In Bengal, women, young, old, married, un-married refereed to as Maa. In the traditional “athpoure” drape, the red border of the saree coupled with the red pola bangle and sindoor is all a part of a deliberate technique. The red border twirls around the body in such a way that it leads your eye to travel to the red sindoor on the forehead of the woman, focussing on her eyes. And the eyes are the most iconic representation of the goddess. The idea being, there is a goddess in every woman,” Dhamija says.

Last year, this year, a pandal in New Delhi’s Chittaranjan Park invited widows to celebrate the pujas along with others on October 19. As young members of the puja committees lead the way in breaking free from age-old traditions.

Women’s traditional dress

Traditional attire for Bengali women is usually the saree, usually made of cotton or silk. While sarees are worn by women across India, the Bengali style of pleating and draping a saree is quite distinct.

Of all the various styles of sarees donned by Bengali women, the quintessential red-and-white sarees – the Korial, the Garad and the Tant – are perhaps the best known, particularly because they are worn en masse during the state’s Durga Puja festival celebrations. However, few people outside the state understand the significance of this particular colour combination. With the white symbolising purity and the maroon or red symbolising fertility, the saree is a celebration of the feminine. The off-white Korial saree usually features a red border and is worn with a red blouse. The Garad is another traditional Bengali saree in the same colour combination, but with a broader red border and printed patterns. Tant sarees are another Bengali wardrobe staple, made of cotton.

But as we all know, Bengal’s saree tradition is richer than the red-and white-variants. After all, the state has a rich history of weaving silk. Of all the many other traditional sarees worn by Bengali women, the Baluchari, Murshidabad and Tussar silk sarees are particularly well known in the rest of the country.

1. Garad & Korial

The term Garad (or Gorod) means white and refers to silk that has been undyed. Garad silk sarees are thus, characterized by a plain white or off-white body, an unornamental coloured border and a striped pallav. The most traditional of garad sarees have a white body and red border and pallav.

The term Korial is derived from the word ‘kora’ meaning plain or blank. Garad-Korial sarees are gorgeous versions of the simple garad sarees. The white/off-white silk base of the saree is plusher and the coloured border and pallav are more ornamental with intricate and elaborate motifs. The richer fabric and the complexity of the weavings add to the grandeur of Garad-Korial sarees.

Garad silk sarees are produced in the Murshidabad district of West Bengal. They are very fine, pure silk sarees, and their texture resembles tissue paper. They are quite light-weight and easy to carry.

Garad, meaning white, is the traditional Bengali saree with a bright red border and stripes in the pallu offset against the un-dyed white silk. Imbued with religious significance, garad sarees (and their cousin- Korial with intricate buti or flower patterns in the body) are hugely popular during the Durga puja, weddings and other religious ceremonies. Paired with the typically Bengali ivory/conch shell and red lacquer bangles, garad sarees are an epitome of grace and authentic Bengali beauty.

https://www.holidify.com/pages/west-bengal-dress-143.html

2. Baluchari Sarees

Balachuri sarees originated in a small place of the same name near Murshidabad district and are made of fine silk. Considered to be heirloom pieces, Baluchari sarees are opulent with gold embroidery of historical and religious scenes from the Indian mythology. They are also called as ‘swarnachari’ sarees owing to their bright gold hue of the embroidery. The elaborate pallu of these sarees is best left unpleated which reveals the full resplendence of the design.

3. Tant Sarees

Deriving their name from the loom on which they are woven, Tant sarees are extremely popular in Bengal. Capable of being draped effortlessly and extremely lightweight, Tant sarees are ideal for the hot and humid climate of Bengal. They are traditionally woven with motifs of paisleys and flowers and carry a thick coloured border. They are an epitome of Bengali handloom culture and perfect for daily wear.

4. Tussar Silk Sarees

Malda district of West Bengal is considered to be the hub of tussar silk production. Tussar silk is more textured than the conventional silk and is also used as a base for weaving elaborate Jamdanis or Balachuris. Apart from this, pure tussar silk sarees are usually characterised by solid colours that are enhanced by a golden sheen of the silk, adorned with both traditional and contemporary motifs on the pallu.

5. Panjabi and Dhoti

The traditional attire for men in Bengal is a ‘Panjabi’, which is the equivalent of north-Indian kurta, paired with a dhoti- a plain loincloth in cotton or silk. Panjabis can be either short or long ending up to knees. What distinguishes Panjabis from the usual kurta is the authentic Bengali fabric that can range from tussar silk, cotton-silk or muga-silk embroidered with kantha around neckline or buttonholes. Garad silk kurtas in the shades of beige, cream and honey are the traditional wedding attire for Bengali men. These days, Panjabi is also paired with jeans or trousers in a unique fusion to blend traditional with the comfortable modern.

Traditional attire for men in Bengal usually consists of the dhoti, a piece of cloth tied around the waist and then wrapped around like a loin cloth between the legs – as is worn around the country. Dhotis are paired with a silk or cotton Punjabi or kurta – a loose fitting shirt which usually goes down to the knees. While white and off-white are the traditional colours dhotis and Punjabis are worn in, today’s Bengali men may take their liberties with colours of their traditional attire.

Textile design involves the process of creating or designing knitted, woven or printed fabrics or surface ornamental fabrics and the aesthetic aspects of an article. An industrial design may consist of three dimensional features such as the shape of an article, or two dimensional features such as patterns, lines and colours. Therefore, an industrial design is the aspect of a useful article which is ornamental or aesthetic.