There are two kinds of embellishments that are created for the crown of Maa Durga’s pratima: Sholar saaj or Daker saaj, of which the former is popularly known as one of the most beautiful handicrafts of West Bengal.

The intricate head-gears of to-be-wed couples, embellished animals, peacock boats, palanquins, the much revered ‘daak -er shaaj’ of Durga idols—all stand as testimony to the vitality of sholapith.

With its elegance and exquisite beauty, the sholapith craft is recognised as one of the finest examples of craftsmanship. The shola reed, having a cultural value, has its own significance, including the fact that since it grows in marshy, water logged areas, this plant is easily available for the artisans to work upon. With its softness, thinness and light weight, the white colour of the material symbolises purity and sanctity. Also keeping in mind the environmental impact, the material is eco-friendly, as it is biodegradable.

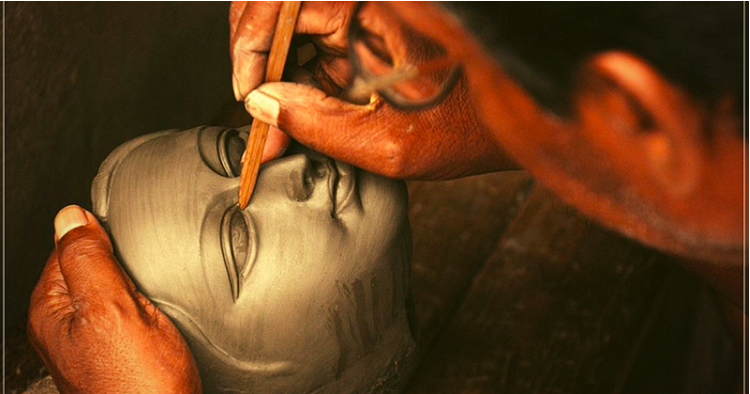

Durga are made of clay with all the deities under one structure, known as “ek-chala” (ek: one; chala: cover). The idol’s eyes not only hold great significance but are painted only in the presence of the sculptor, a process known as Chokkhu daan (offering of the eyes).

“In ‘Ek Chala’ idols, goddess Durga and her four children — Kartikeya , Ganesha , Saraswati , and Laxmi — are all sculpted in one frame known as ‘chal chitra’.”

Sholapith Work

“Sholapith work is popularly known as ‘Sholar Kaj’. The people engaged as sholapith craft are known as Malakar, meaning ‘maker of garland’, probably because they made garlands made of shoal for idols and for the noble class.

The Malakars belong to the Nabasakha group of artisan class and they are involved in this craft from generation to generation. The nine craft communities are: Kumbhakar, Karmakar, Malakar, Kangsakar, Sankhakar, Swarnakar, Sutradhar, Chitrakar and Tantubaya. According to the Brahma Vaivarta Purana, their ancestor was born of divine Viswakarma and pious Sudrani mother Ghritachi, a cursed Gopi girl. Their progeny were named as Malakar. In Brihad Dharma Purana, the Malakars are referred as the progeny of Brahman father and Vaisya mother.

“The Malakars believe in their divine origin ~ they are the descendants of Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati. There is a legend behind the use of shola crafts in India.

It is said that while going to wed Himalaya’s daughter Parvati, Shiva desired to wear a conical white hat. As the celestial artist Vishwakarma began looking for an appropriate material to make the hat, a kind of plant grew in the wet land as desired by Shiva. This was the shola or sponge wood plant. But Vishwakarma was used to working with only hard materials like stone or wood and not with soft shola.

Once again at Shiva’s desire there appeared in the marsh a handsome young man and he was named Malakar. All those who are now connected with the shola craft are thus known as Malakars and belong to the Hindu community. Malakars worship Shiva as they believe they owe their existence to Shiva and, therefore, are obliged to worship him.”

Clay idols of Kumartuli: A case for geographical indication: Indian Express (11th September 2020)

A GI tag can be a first step towards recognising the distinctive artistic talent of this remarkable social group of potters and prevent their unique craft from disappearing into oblivion.

North Kolkata, West Bengal, is a 300-year-old quarter of traditional potters.

The establishment of Kumartuli (or potters’ locality) can be traced to the Battle of Plassey and the advent of the East India Company, which allotted separate districts to workmen. These districts were gradually identified by the predominant activity, example, Suriparah (the place of wine sellers), Aheeritollah (cowherd’s quarters) and Coomartolly (potters’ quarters) and so on.

Idol-making is dependent on various local ingredients such as hay from the Sundarbans region, the supply of which has dwindled. Clay is the main ingredient; entel mati is an expensive variety while bele mati is cheaper. Dresses, ornaments and sholapith artifacts are made by craftspersons from various parts of Bengal. Golden and metallic foils are procured from Surat.

In recent years, the annual Durga Puja has created space for the ‘theme artist’ and pandal-making is a creative art dwelling on many eclectic themes. Décor, artwork and illumination are important components of a community puja and a source of livelihood for traditional electrical artists from the former French colony of Chandernagore and for associated craftspersons from various districts.

The clay idol-making small cottage industry has thus created a large ecosystem of supporting crafts, which are mostly environment-friendly. Idols are also artistically created using jute, paper, matchsticks etc., though not necessarily by the Kumartuli artisans. Clay idol-making processes involve entire families. Dependence of this industry on small businesses helps support other livelihoods. The demand for Kumartuli idols within India and in the overseas markets has an intrinsic growth potential due to the environment-friendly dimension of the craft. Most artisans belong to disadvantaged communities which need support and encouragement as part of the overall effort towards inclusive growth.

How will a Geographical Indication (GI) status under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, help?

The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, November 2001, reaffirmed that “culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs”. It further noted that, “culture is at the heart of contemporary debates about identity, social cohesion…” “(Trade and Culture” Seriously: Geographical Indications and Cultural Protection In WTO Law, Tomer Broude)

The Kumartuli potters have resided in the Kumartuli colony for hundreds of years. The unique cultural value of clay idol-making here is derived from age-old knowledge and skills of the idol makers, the artwork in the iconography, the laborious processes involved and the religio-cultural significance of Durga puja in Bengal. Uniqueness lies in the application of technique with skilled hands. The raw materials are locally available products and the skills required for moulding clay, painting, decoration etc., are in the realm of intangible knowledge which has been passed down from earlier generations and adapted to the needs of the market in innovative ways. Kumartuli is thus a unique repository of traditional cultural knowledge. (WHY GI SHOULD BE GIVEN)

Sadly, this unique traditional craft in Bengal has not been suitably recognised or supported. While Bankura Panchmura Terracotta Craft, Purulia Chau Mask, Bengal Dokra and Bengal Patachitra, etc., have been granted the GI tag, the Kumartuli clay idols, surprisingly, are yet to figure on the GI Registry. The clay artisans work in miserable conditions and suffer from financial crises, particularly during the lean season. Prices of idols do not cover costs, which have increased over the years. Large numbers of artisans trained in this craft perforce look for odd jobs. In the years to come, this can have adverse implications for the Sharod Utsav. The calamitous situation of the pandemic and the aftermath of the Amphan cyclone have affected the livelihood of these clay artists as their idols have either suffered damage or remained largely unsold. Interventions for supporting the community are required now, more than ever before.

The registration of a geographical indication shall give to the authorized user or users, the right to obtain relief in respect of infringement of the geographical indication under the GI Act. The authorized user shall have the exclusive right to the use of the geographical indication in relation to the goods for which the GI is registered. GI products generally command a premium.

However, for realising the full benefits of such a registration, other targeted interventions will be necessary, especially in production, crafts preservation, marketing and welfare of artisans to sustain their creativity. (Indian Handicrafts Directions for State Intervention, MV Narayana Rao). Kumartuli can be developed as a sustainable socio-cultural heritage area through a robust multi-pronged strategy in mission mode with concerned stakeholders. A comprehensive database on number of potter families, master idol makers, junior clay artists, outsourced artisans, number of work sheds, etc., if properly researched, can aid overall policy planning.

The formal creation of a ‘Kumartuli Crafts Village’ like perhaps Raghurajpur near Puri in Odisha, with a boundary wall and up-gradation of basic infrastructure can be a next step. Raw material depots within the village can ensure easy availability of basic inputs. Other critical infrastructural support systems must include improvements in work-shed amenities (lighting, ventilation) and dwelling quarters, creation of a large common facility for storage of finished images and a waste disposal facility, besides improvement in roads, drainage systems, street lighting, etc., within the colony. Schemes under the Ministry of Textiles can support some of these interventions.

For crafts preservation, awareness about the craft can be disseminated through a dedicated portal with information on individual artisans and their unique skills, besides the history, artwork and religio-cultural beliefs associated with the festival it supports. A ‘Clay Idol Crafts Museum’ in the Crafts Village can display innovative creations and the contribution of the ‘theme artist’.

Linking the Crafts Village with tourist circuits and with e-marketing platforms can fetch better price realizations for the idol-makers. To develop export markets, the association of potters can be registered as a ‘Producers Society’ and suitably assisted to acquire membership with the Handicrafts Export Promotion Council.

Older idol-makers need recognition and support under credit schemes and old-age pensions. Schemes for life insurance and credit access implemented for the handicrafts sector by the Ministry of Textiles can be leveraged. Education and skilling of children of these families must be prioritised and supported through special schemes which can encourage them to carry on with this great tradition.

A GI tag can be a first step towards recognising the distinctive artistic talent of this remarkable social group of potters and prevent their unique craft from disappearing into oblivion.

+ Copyright for the Idols, apart from GI as it is a sculpture and design if it is ek chala or based on a theme.